It’s Black History Month here in the United States! Black History Month or African American History Month is the month of the year where we nationally celebrate, embrace and promote the achievements and accomplishments of Black and Brown people, which too often are hidden from our curriculums and history books. Although it was nationally recognized in 1976, Black History Month has it’s roots over 100 years ago in 1915.

At Stitch People we’re celebrating Black History Month and BIPOC history! In typical Stitch People style, we’ll of course have brand new patterns. Also, every day this month, we’ll be featuring the story and influence of Black and Indigenous who have inspired, changed, or moved the world. Click the links below to read more each day:

February 5th Matthew Alexander Henson

February 6th Samuel Coleridge Taylor

February 11th Learie Constantine

February 12th Albert Namatjira

February 13th Zelda Wynn Valdes

February 15th Thurgood Marshall

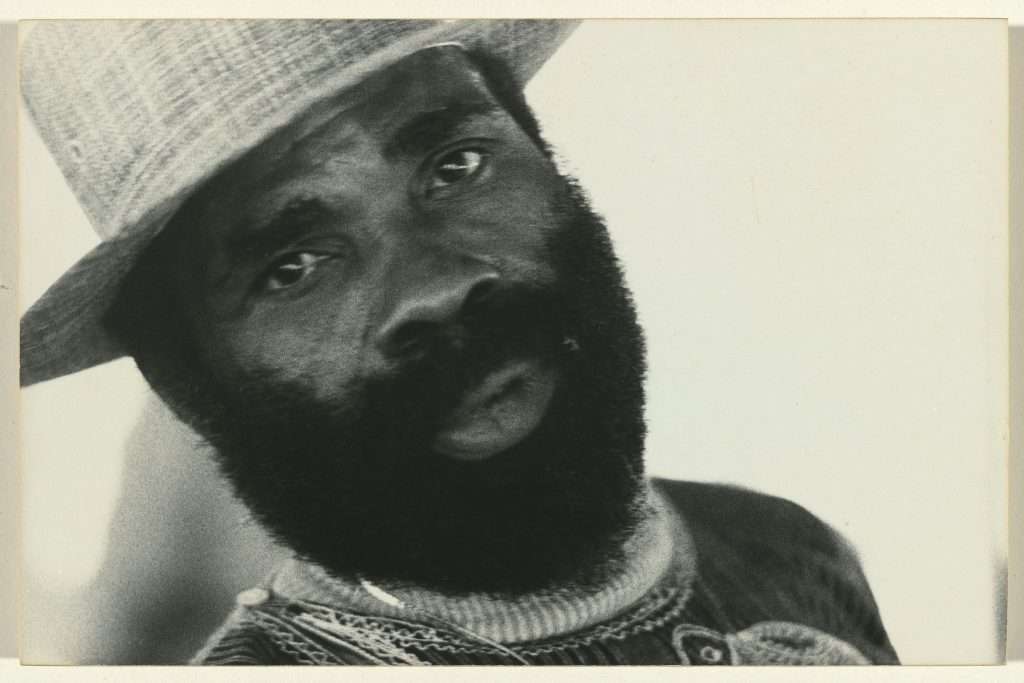

February 19th Ambrose Campbell

February 22nd Buffy Sainte-Marie

February 25th Evonne Goolagong Cawley

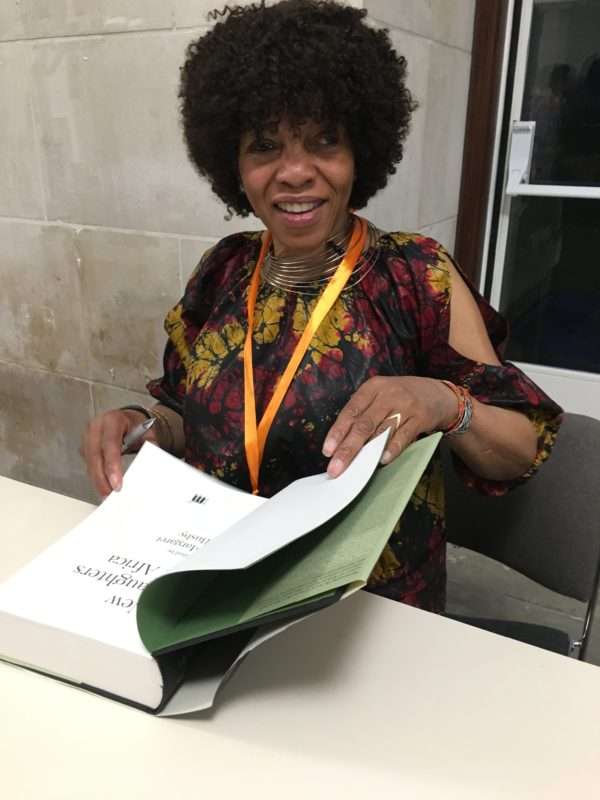

February 27th Shirley Thompson

We have dedicated a brand new (and fabulous) pattern set where you will not only find a Stitch People pattern of each of the people we feature this month, but also never before seen accessories and backgrounds unique to that person’s story!

100% of proceeds from this pattern set will be going to Crafting the Future! Crafting the Future work to diversify the fields of art, craft and design by connecting BIPOC artists with opportunities that will help them thrive.

Click here to purchase and download the patterns!

More you say?! Well if you insist! We are also celebrating each of the historical (and present day) figures with a FREE pattern available for download here.

This free pattern will be the subject of our very first open Stitch People stitch-a-long. Every day of the month, we’ll be stitching a different person from our free Black History Month pattern. Stitch-a-long participants will receive an email prompt everyday with the person we’ll be stitching, links to more information about them and a daily quote or action you can take to learn more.

Sign up to the Stitch-a-long here!

We hope you’ll join us in our celebration of Black History Month. Tag @stitchpeople in your cross-stitch celebrations on Facebook or Instagram!

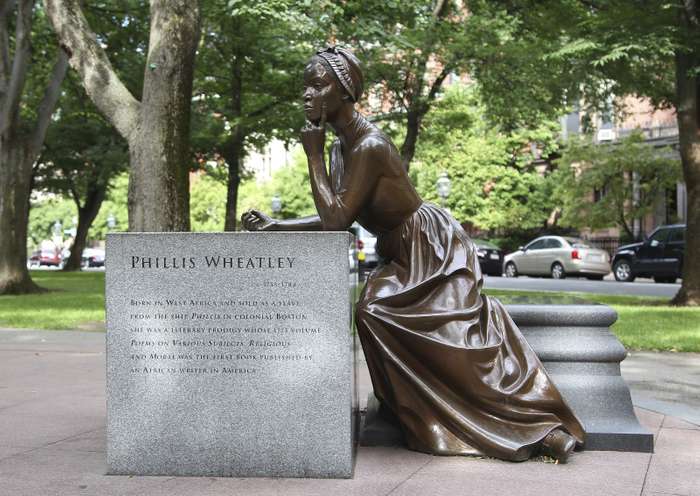

February 1st Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley was a pioneering poet spending most of her life in Boston, in the mid 1700’s. Her moving and eloquent poems centered around Christianity, war, her pride in American independence, the culture she was subjected to and her African heritage. Her talent for poetry was so exemplary, she was only 13 when her first poem, “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin,” was published. The publication of poems under her name was a magnificent feat. Not only because of her young age but because of her gender and that she was an enslaved person, afforded none of the rights of other writers of her day.

As you can imagine this achievement did not come easy and was the result of an exploited and unusual life. Phillis Wheatley was born around 1753. We do not know the exact date as it was her “usefulness” that was considered worth recording, not her birth. It was approximated that she was about 7 or 8 when she taken captive by slave traders and taken to America. In 1761 she was purchased by her enslaver John Wheatley as a servant for his wife. It was contemptibly noted she was purchased “…for a trifle” due to her fragile and sickly physical health. She was later diagnosed with severe asthma. She was given the name Phillis after the ship that carried her from her homeland, “the Phillis”, and as was custom took the last name of her enslaver, Wheatley.

It was at this point that her life took a turn that was unusual for an enslaved child of her day. Although still required to perform the duties of an enslaved domestic servant, she was considered quick witted and after a time was taught to read and write. Showing an aptitude for academics, she began to study the Bible, astronomy, geography, history, British literature, Greek and Latin.

When she was approximately 16, Wheatley wrote “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield ” which was published in 1771 this poem brought her international acclaim. An acclaim her enslavers were quick to take advantage of by advertising for subscribers of a collection of Wheatley’s 28 poems. When colonizers seemed unwilling to support the work of an enslaved person, the Wheatleys turned to Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon in England: a wealthy supporter of evangelical and abolitionist causes. As a result of a positive response to her token presentation as “the African genius” in England, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral“, the first volume of poetry by an African American was published in England in 1773.

Wheatley continued to write and publish her work and letters which very often celebrated a hopeful future for America as a result of its independence from the colonies. This resulted in attention from high ranking abolitionists, clergy and members of colonizer society circles. In 1776 Wheatley was invited to have an audience with George Washington, (who later became first President of the United States), at his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Even at the most popular point in her career, Wheatley was always considered a servant and at all times kept at a distance from “respectable” colonizers. Still, until her early adulthood she had been spared much of the turmoil and violence, others in her position were experiencing. She was criticized later in history for not speaking out against slavery at the time of her writings (although this was recently proven untrue). This unusual start to life may have left her unprepared for her few remaining years.

In 1778, Wheatley was manumitted and shortly after married freed Black grocer, John Peters. Wheatley’s husband was ambitious, talented and educated however, due to the racist realities of the time he was considered arrogant and prideful. The couple struggled to find employment for many years, soon slipping into poverty, losing 2 children in infancy and Peters to debtors prison. During this time, Wheatley continued to write and publish her poetry with the faith that her evangelical supporters would welcome another volume of her work. The American society however, did not share her faith and refused to support a publication of her work. In fact, her first volume of work was not published in America, until two years after her death.

It was a sad ending for Phillis Wheatley. She died in poverty and sickness at the age of approximately 31. Devastatingly followed shortly after by her 3 month old son. Wheatley has been credited with over 145 beautiful poems in her short life however there may have been many more that have been lost through time. Although she has a desperately sad and short life, Wheatley’s innate talent has left a mark through history and a legacy of passionate and moving words that allow us to hear her voice to this day.

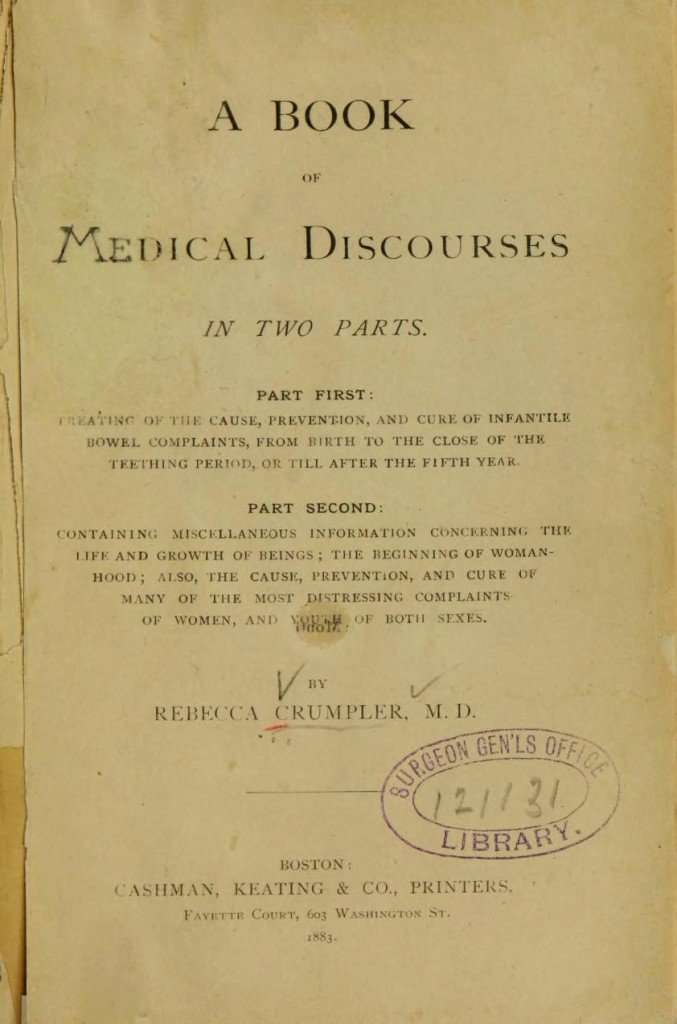

February 2nd Rebecca Crumpler

If you imagine what you would want in a doctor, Dr. Rebecca Crumpler would be it. History paints her as someone who truly cared about the well-being of all people but particularly those who most needed her help. She sought out opportunities to care for people who had little access to medical care, focused on the medical health of women and children (a field neglected by most physicians of the time) and forged through racist and sexist barriers to make sure those people recieved the best treatment she could provide.

As with many pioneers of Color, Dr Crumpler’s accomplishments were not widely celebrated until much later in history. As a result, much information about her life has been lost or was never recorded. What we do know has come from her own words in the medical book she authored.

Dr. Crumpler spent her childhood with her aunt in Pennsylvania. In Crumpler’s words her aunt’s:

“…usefulness with the sick was continually sought, I early conceived a liking for, and sought every opportunity to relieve the sufferings of others,”

As a teenager, Crumpler attended the West Newton English and Classical School in Massachusetts where she was a special student in mathematics.

By 21 Dr. Crumpler had married and began work as a nurse despite having no professional training. In fact, the first nursing school in the US was not open until 1873.

“I devoted my time, when best I could, to nursing as a business, serving under different doctors for a period of eight years (from 1852 to 1860); most of the time at my adopted home in Charlestown, Middlesex County, Massachusetts,”

Dr. Rebecca Crumpler

Her medical empathy and excellence resulted in recommendations from her physician employers for admittance to New England Female Medical College for which Crumpler won a scholarship. After the civil war when Crumpler attempted to return to medical school, her scholarship had been rescinded. Fortunately, Crumpler was instead able to take advantage of a scholarship award from the Wade Scholarship Fund established by the abolitionist Benjamin Wade and was able to return to her medical studies which otherwise she would have been prevented from.

Although it was considered “unladylike” for women to practice medicine (it was a common thought that women’s brains were 10% lighter than men’s and thus could not handle the rigors of medical practice), the need for medical doctors during and after the civil war necessitated a short detour from misogyny. Still at the time of Dr. Crumpler’s graduation in 1863, there were only 300 female doctors compared to over 54 000 male in the United States. Dr. Crumpler became the only African American among them. Crumpler completed her medical degree in just 4 years during which time she grieved the loss of her husband to tuberculosis.

In 1864, Dr. Crumpler married Arthur Crumpler and in 1865 moved to Richmond where Dr. Crumpler took a position with the Freedmen’s Bureau, caring for newly freed slaves. Crumpler declared of her work there as:

“a proper field for real missionary work, and one that would present ample opportunities to become acquainted with the diseases of women and children. During my stay there nearly every hour was improved in that sphere of labor. The last quarter of the year 1866, I was enabled…to have access each day to a very large number of the indigent, and others of different classes, in a population of over 30,000 colored.”

Dr. Crumpler was loved by her patients, but shunned by her peers. Racist slurs were hurled around, her professionalism questioned and prescriptions refused.

For years Dr. Crumpler endured until 1869 when they returned to her home of Boston. There she continued her practice from her home, caring for those in need, many who could not afford medical care.

From what we know, Dr. Crumpler continued her practice until 1880 where she moved from Boston to New York. There she authored her book “A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts,” published in 1883. She dedicated this book “to mothers, nurses, and all who may desire to mitigate the afflictions of the human race.”

Dr. Rebecca Crumpler died on March 9, 1895, in Hyde Park.

There’s no telling how many families owe their existence to Dr. Crumpler’s perseverance, skill and desire to help those in need. Not only those who benefited from her direct care, but those who were inspired to pursue their own careers in medicine and then those who benefited from the inspiration of her legacy. In 1989, the Rebecca Lee Society was established to be one of the first Black medical societies exclusively for women. This society led to the support and promotion of other Black women physicians caring for those in need to this day.

Want to dive deeper into the life of Dr. Rebecca Crumpler. We found this book for you to read!

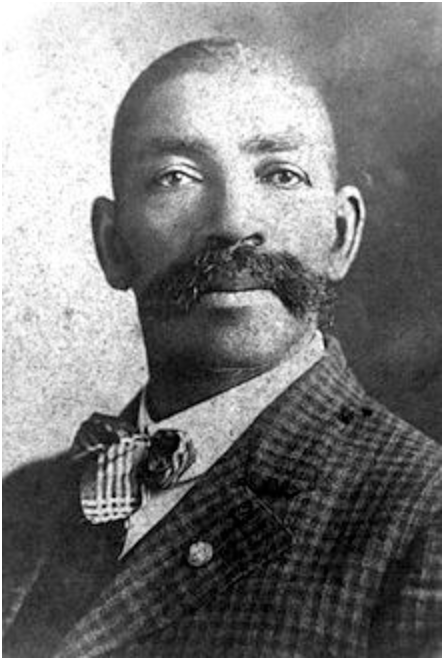

February 3rd Bass Reeves

Have you ever seen those old Lone Ranger TV shows…you know the ones “Hi Ho Silver…AWAY!”. Yes, those. Well, it has been proposed that that gallant character was based in part on the infamous Bass Reeves. Bass Reeves was what you might consider a stereotypical hero of the old West and during his time was revered for “always getting his man”.

Born in 1838 Bass Reeves was named after his grandfather, Basse Washington. As was custom, he was given the surname of his enslaver, Arkansas state legislator William Steele Reeves. Bass Reeves bondage was passed down to his enslaver’s son George Reeves. At the break out of the civil war, George and Bass Reeves headed to the confederate army. This is an important turning point in Bass Reeves life. It’s not clear exactly how it happened but somehow Reeves obtained his freedom from his enslaver. It is rumored that at the end of an ugly card game, Reeves was able to escape bondage by severely beating his enslaver and escaping to Indigenous Territory where he lived with, learned the language and customs of the Cherokee, Creek and Seminole Nations. This would give him a distinct advantage in the years to come.

At the abolition of slavery in 1865, Reeves moved to Arkansas where he married, raised children and farmed. BUT during this time, the Old West was a tumultuous region, writhing with lawlessness. Having heard of Reeves tracking ability and that he was able to speak several Indigenous languages, then U.S. Marshall James Fagan sought out Reeves as one of 200 marshalls for the territory. Accepting this position made Bass Reeves, the first African American deputy U.S. Marshall in the United States.

From 1875 until 1907, Reeves was prolific in the detaining and capture of over 3000 wanted people, often using disguises as a means of getting close to the people he was after. Reeves famously rode a white horse and was known as one of the greatest marksmen and detectives of his time. Sound familiar? Throughout these years he was never injured.

Reeves was one of if not the most feared deputies over the 75 000 mile territory. Not for his personality, he was said to have been personable and enjoyable company; but for his success rate in apprehending even the most dangerous of wanted people. One of those was outlaw Bob Dozier – a jack-of-all-trades kind of criminal who fell victim to Reeves pistol.

One of the saddest of Reeves’ cases was his own son Bennie, who was charged with murdering his own wife in a fit of jealousy. Though shaken, Reeves accepted responsibility for the apprehension of his son, returning with him just two weeks later to be tried for the murder of his wife.

35 years of Reeves’ life were spent “cleaning up” the Old West. In 1907, Reeves retired and just 3 years later, succumbed to Bright’s Disease leaving 12 children.

Want to read more about the life and times of Bass Reeves? Head to this link and for more, this book by the same author

February 4th Elijah McCoy

Imagine if you will, a little boy of 7 or 8 sitting beside one of the newly built railroads that sliced through Indigenous lands in the mid 19th century. He stays by the railroad for a time and finally sees what he’s been waiting for. The puff of steam that indicates something special is coming. Soon he feels the ground moving and leaps to his feet. In a flash, a thunderous monster, ten times his size comes barrelling towards him and in no time is flying past. The wind it creates almost knocks him to the ground. The boy stands in awe of the power and size of this fascinating man-made machine as he watches it fade into the distance. This is what we like to imagine was the spark of love for engineering in the heart of Elijah McCoy, and soon led to a lifetime of invention, which drastically changed the industrial landscape of the United States.

Elijah McCoy came from a family that were familiar with railroads of a completely different kind. His mother and father had risked everything and traveled the underground railroad to escape enslavement in Kentucky. Through what we can only imagine was a traumatic and terrifyingly long and arduous journey, his parents arrived free in Canada. They settled in Colchester, Ontario and on May 2, 1844 Elijah McCoy was born. McCoy was part of a large family, with 11 brothers and sisters. His father, George McCoy served in the British Military and was awarded 160 acres of land for his service. This was where the family stayed until 1847 when the family moved to the free state of Michigan. From Detroit the family moved to Ypsilanti, there they opened a tobacco business.

McCoy showed an early love of tools and machinery, often experimenting and finding different ways to fix or improve them. Seeing the potential in their child, McCoy was sent at the age of 15 across the world to Scotland. Here he apprenticed as a mechanical engineer, filling his brain with the knowledge he would later use to change the world.

Upon his certification, McCoy returned to his family and began looking for work as a Mechanical Engineer. Although highly qualified and skilled in his trade – you guessed it – the other powerful, man-made but progress eroding machine – racism, prevented McCoy from taking a professional position for which he was most qualified. This must have been heartbreaking for McCoy whose naturally inquisitive and inventive mind would have flourished in such a profession. Instead McCoy found a position for the Michigan Central Railroad as locomotive fireman and oiler. A position that wouldn’t have required the high level of qualifications that McCoy had.

Trains at the time were not the most efficient of machines. They were reliant on tons of oil and coal to run. Due to the constant moving parts, they often would overheat and required regular manual oiling to prevent them seizing up. This was one of the responsibilities of McCoy’s position. As they say ‘necessity is the mother of invention’! After realizing the inefficiencies of the existing system of oiling axles, McCoy used his skills to invent a lubricating cup that distributed oil evenly over the engine’s moving parts. This allowed trains to run continuously for long periods without having to pause for maintenance. To say the least, this was revolutionary for the railroad industry. McCoy received a patent for this invention in 1872. The first of 57!

Soon, trains, transatlantic ships, oil drilling and mining equipment and factory machines were all using his lubricating invention. Michigan Central Railroad promoted McCoy to instructor in his new inventions, and later he became a consultant to the railroad industry on patent matters.

It wasn’t just train parts McCoy invented, patents of his have been found for many other machines but also household inventions such as folding ironing boards and lawn sprinklers. Lacking the funds to manufacture his own inventions, McCoy often sold them to investors or assigned patent rights to his employers. This meant his name did not appear on the majority of products that he created. However, towards the end of his life McCoy formed the Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company which produced lubricators bearing his name.

One of most interesting theories about McCoy’s prolific career was that desire for his lubricating technology was the origin of the term “the real McCoy”. It was said, his technology was so sought after, engineers did not want cheaper knock-off lubricators – they wanted “the real McCoy”. Although some contest this was not the origin of the term, it was certainly a term uttered by many an engineer who wanted their equipment to run efficiently for years.

Another interesting fact (especially for those who have been following our Black History Month features) is that McCoy’s wife, Mary was a prominent activist for civil and women’s rights. Inspired by Phillis Wheatley, (who was our very first Black History Month feature!) Mary and Elijah McCoy both helped to found the Phillis Wheatley Home for Aged Colored men in 1898.

McCoy had a long life of ingenuity and invention and worked almost up until his dying day. In 1922, he and his wife were in a serious car accident. Mary did not survive. McCoy was left with very serious injuries which contributed to his death on October 10th, 1929.

McCoy literally changed the world. His invention made it possible for the railroad expansion across the United States. Not only this, the invention led to progresses in machinery and hauling technology across the entire world. As such his name became associated with invention, engineering and mechanical progress. Booker T. Washington cited McCoy in his “Story of the Negro” as the Black inventor with the greatest number of U.S. patents. In 2001, McCoy was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. A historical marker stands outside his old workshop in Ypsilanti, Michigan, and the Elijah J. McCoy Midwest Regional U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in Detroit is named in his honor.

For better or for worse, the industrial revolution and the expansion of capitalism would not have been able to evolve and progress as quickly without him. That little boy, standing by the railroad, would soon carry a weight far greater than the trains we imagine he was so fascinated with at the very beginning of his journey in life.

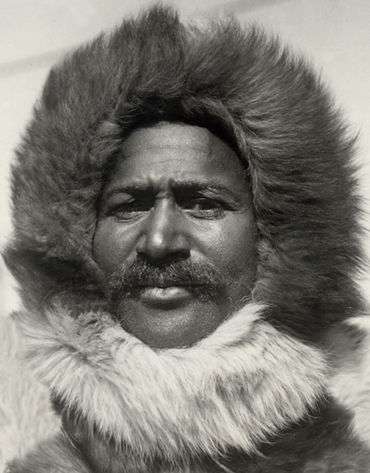

February 5th Matthew Alexander Henson

Frozen toes, hypothermia, ice floes and snow storms is not something a usual person seeks out in life, but Matthew Alexander Henson was not your usual person. He was an adventurer in the truest sense of the word.

Henson was born in 1866 in Charles County Maryland. His parents were sharecroppers. As with many families of color in the region, Henson’s family were subject to constant attacks and harassment by white terrorist groups in the area. The family were forced from their home and moved to Georgetown just a year after Henson’s birth.

Henson had only a few short years with his mother, she passed away when Henson was only 7. His father remarried but also passed away not long after his first wife. Henson was sent to live with his uncle who sent him to public school for a short time. While attending school, Henson also worked in a restaurant kitchen, washing dishes. During these early years, Henson attended a ceremony honoring Abraham Lincoln. During this ceremony a speech was given by activist and orator Frederick Douglas, encouraging Black men and women to vigorously pursue educational opportunities and battle racial prejudice. This calling moved the young Henson and he took the words to heart.

His uncle passed away a few years after Henson’s arrival. Having experienced so much death at such a young age, Henson was eager for life to begin. Henson walked on his 12 year old legs, to Baltimore, Maryland. This is where his adventures began.

By many accounts, Henson was quick to smile with a welcoming personality. These skills came in handy for a boy alone in the world. Henson found work as a cabin boy on the merchant ship Katie Hines. During the following years, Henson travelled the entire globe. This young boy soon to be man saw new worlds and cultures including China, Japan, Africa, and the Russian Arctic sea; places other boys his age would only dream of. Befriending the ships leader, Captain Childs, Henson was taught to read and write.

Henson’s time on the Katie Hines ended and he found himself back in Washington D.C. Henson found a position in the clothing store B.H.Stinemetz and Sons. There he met a man who would change his life and called to Henson’s adventurous spirit, explorer Robert E Peary. Henson would recount stories of his seafaring days to Peary. Having much in common, the two became friends and Peary hired Henson as his personal valet. Their first expedition together was to Nicaragua and this would be nowhere near their last.

Between his adventures, Henson married however due to the long stretches of absence, the marriage did not last. Henson married again in 1907. During his long expeditions, Henson lived with the Inuit people Ootaq, Egingwah, Sipsu and Ooqueeah. Living with the People of the North, Henson learned to speak their languages fluently. He learned how to survive in the harsh conditions of the Arctic, how to hunt and fish, how to sled and work with arctic dogs. Henson essentially became one of the Inuit People, even going so far as to form a relationship with one of the women, Akatingwah. Akatingwah and Henson had a child together, a son named Anauakaq. Anauakaq was and remained Henson’s only child.

Between 1891 and 1908, Henson and Peary made several attempts to reach the North Pole. This was an obsession for many explorers during the time. Henson and Peary were no different and in 1909 it would seem they conquered that obsession. A giant crew of 22 Inuit men, 17 Inuit women, 10 children, 246 dogs, 70 tons (64 metric tons) of whale meat from Labrador, the meat and blubber of 50 walruses, hunting equipment, and tons of coal departed Greenland to Cape Sheridan. From there, the Inuit men, Henson, Peary and 130 dogs worked to lay a trail and supplies along the route to the Pole. Then, with 4 Inuit men, Peary and Henson set out to reach the North Pole.

During their arduous journey, Peary became ill and could not go on. Henson went ahead as a scout and soon, he became one of the first humans to reach the furthest north. Now, we would say he reached the North Pole, however since then, there has been a lot of debate surrounding whether it was actually the North Pole that he reached. Henson declared it was and planted an American flag as for some reason is custom with explorers. Henson returned to fetch Peary. Realizing that it was Henson who may have reached the North Pole first, Peary became angry. This caused a rift in the 20 year friendship the men had built.

Regardless of whether the North Pole was actually reached by Henson, this was a huge achievement for humanity. We can’t imagine what these 6 explorers went through on this journey. Henson had kept the words of Frederick Dounglas close to his heart and excelled, breaking physical, racist and personal barriers. Laying a trail for other explorers such as George W. Gibbs, Jr. first African American to set foot on the continent of Antarctica.

In 1912, Henson wrote his autobiography “A Negro Explorer of the North Pole”. After this time, a life of adventure slowed down as Henson became a clerk in the U.S. Customs House. A post he held until retirement in 1936. In 1937 he was the first African American to be made a life member of The Explorers Club. 10 years later he was elevated to the club’s highest level of membership. In 1944 Henson and the other expedition members were awarded the Peary Polar Expedition Medal. As a final honor, 33 years after his death in 1955, Henson and his wife were re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery. In 2000 Henson was posthumously awarded the Hubbard Medal by the National Geographic Society.

Want to hear about Henson’s life in his own words? Click here to listen to “A Negro Explorer at the North Pole” as an audio book.

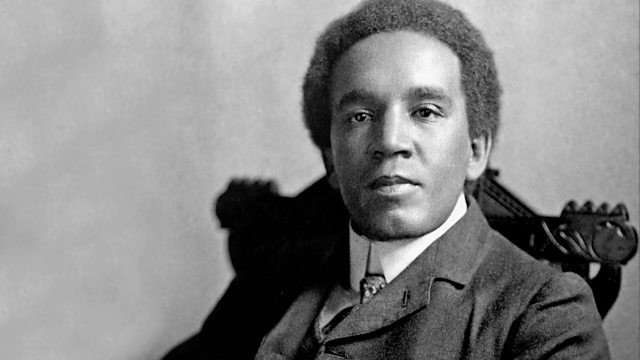

February 6th Samuel Coleridge Taylor

For our next Black History Month feature, travel with us all the way to 19th Century England and visit with Samuel Coleridge Taylor. Samuel Coleridge Taylor was one of the most talented musicians and composers of his time.

First we should start with his parents because their history, particularly his biological father would heavily influence Taylor’s work. His father, Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, was born and raised in Freetown, Sierra Leone a colony established for the freed enslaved of British colonies across the globe. There his father went to school and developed a desire to practice medicine. At the age of 19 he was sent to study medicine at King’s College in London graduating 4 years later and beginning a solo practice in Croydon, an area of London. At some point during these years, Hughes Taylor met Alice Hare Martin. There is no record of a marriage between the couple but we can assume it was a short romance. After his practice failed to be supported by the locals, he returned to Sierra Leone a few months before Samuel Coleridge Taylor was born in 1875. There he became a successful coroner and began another family. He died at the age of 57.

Taylor’s mother, Alice Hare Martin was born to Benjamin Holmans and Emily Ann Martin in 1856. By most accounts they were a close and loving family. Not much is known about Alice up until she met Taylor’s father. At that time she was 18 or 19 and living with her father in London. In 1875, when she was 19 she gave birth at home to Samuel Coleridge Taylor.

During his early years, Samuel Coleridge Taylor (known as Coleridge to the family) lived with his grandfather and mother. He was said to be a quiet child who enjoyed playing with marbles but wasn’t much for socializing with the other children at school. His grandfather was either a Farrier or a Blacksmith (there are different accounts) but he was also a lover of music and himself played the violin. After taking an interest in the violin, his grandfather began to give Taylor lessons. His talent for music was noticed immediately. Taylor’s grandfather saw a bright future in music for his grandson and paid for the six year old to take music lessons.

‘When I was about a year old my mother removed to Croydon, and there I have since lived for thirty-two years. My first teacher in music was my maternal grandfather, Mr. Benjamin Holman, who gave me some lessons on the violin when I was quite a child. I afterwards became a pupil of Mr. Joseph Beckwith, who may be able to tell you something about my early days.’

Samuel Coleridge Taylor

Taylor has other influences of music in his life. He had an uncle in the resort town of Folkestone who was a professional musician. They both occasionally played concerts together. He was also encouraged to sing and play violin in the school choir, and sang in the local church choir. He drew the attention of Herbert Walters, the choir master of the local church who then gave Coleridge lessons in singing and piano. From working occasional jobs as a musician, Taylor saved enough money to buy a piano of his own at 14. Soon he was solo chorister at the church. During his years in the choir, he was first exposed to professionally composed classical music. There in Croydon, Taylor began to form a musical career and strong reputation for musical talent.

At just 15, Taylor was accepted into the Royal College of Music, news that would overjoy his grandfather who had nurtured Taylor’s talents from just a little boy. Attendance at the college was a whopping £40 per year. Bear in mind, a good wage in those days was about £1. Knowing how the boy would benefit from tutelage, both Taylor’s violin teacher and his choir teacher guaranteed his attendance and what a blessing that was because this was where Taylor truly flourished!

I decided, with his mother’s consent, upon a musical career for him, feeling quite sure in my own mind that he would make his mark. After a long and encouraging talk with my dear old friend Sir George Grove, he was entered as a student at the Royal College of Music in September 1890, taking the violin as ‘first study’.

Jeffery Green – Taylor’s first violin teacher

Two years into his studies Taylor switched to composition and continued to learn to play a variety of instruments. This was when his first compositions were created and first had work published and performed in public! It was said at the time:

His characteristic gift for melodic beauty is always present.

It was at this time, Taylor met his future wife Jessie Walmisley, a talented pianist. They were married Dec. 30, 1899 and later had two children Hiawatha and Avril.

After his graduation, Taylor began teaching, performing, conducting and all the whole composing. It was in 1898 that he would compose the works he was most known for:

Ballade in A Minor and most famously Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast based on poems American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast alone would be performed hundreds of times all over the world in just the next 15 years. It also inspired the name of Taylor’s first child.

Taylors obsession with music meant he sought out compositions of all kinds. In 1899 Coleridge-Taylor first heard American spirituals sung by the Fisk Jubilee singers on one of their tours. He became interested in African-American folk song and began incorporating it into his compositions. in 1901 he wrote 24 Negro Melodies. This impressed the African American society and as a result a 200-voice African-American chorus was founded in Washington, D.C., named the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Society. It was during this time he became friends and collaborators with African American poet and author Paul Laurence Dunbar. The two would share an interest in civil rights and African heritage. Not knowing much about his father, this inspired Taylor to learn more about the African diaspora and his heritage. This influence showed up in his later compositions.

In 1904, Taylor began the first of what would be three hugely successful tours of North America. The Coleridge-Taylor Society, an African American choir, appeared with the United States Marine Band, with the composer at the podium. During his stay in the capital Coleridge-Taylor visited President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House.

In May and June 1910 he made his third and last visit to America. Boston, Detroit, New York, and Connecticut were on his schedule. He was the guest conductor at the Litchfield County Choral Union Festival at Norfolk, Connecticut. Such was his fame that just two racist whites withdrew from what they perceived as the humiliation of working under a black.

Jeffrey Green

Taylor was the most incredible hard worker. Despite his fame, composers of his time were not paid well. They typically received a very small sum for performances and often sold the rights to work outright which left them no income from royalties. Taylor’s most popular work Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast made thousands but Taylor received just 15 guineas. This meant in order to support his family, Taylor took on whatever work he could whenever he could. It’s said that this is what contributed to his death and just 37 years old. On September 1st, 1912, Samuel Coleridge Taylor passed away of pneumonia leaving a wife, two children the world bereft of any more of his beautiful music.

Too young to die: his great simplicity, his happy courage in an alien world, his gentleness, made all that knew him love him.

Alfred Noyes

Due to the popular belief that over work in order to keep his family in financial stability, King George V granted Jessie Coleridge-Taylor, the young widow, an annual pension of £100, evidence of the high regard in which the composer was held. In 1912 a memorial concert was held at the Royal Albert Hall and garnered £300 for the composer’s family. Knowing that he and his family had received no royalties from his Song of Hiawatha, which was one of the most successful and popular works written in the previous 50 years. Music appreciators and other professional musicians formed the Performing Rights Society. This was in an effort to gain revenues for musicians through performance as well as publication and distribution of music.

Samuel Coleridge Taylor left the world but his passion for music lived on in his children. Both Hiawatha and Avril became successful musicians, filling the world with their father’s influence for years after his death. Even now over 100 years later, his talent and reputation live on as musicians all over the world play the beautiful sounds he gifted us all those years ago.

February 7th Oscar Micheaux

The next time someone tells you that all you need is a ‘can do’ attitude, we hope you think of Oscar Micheaux. He took the idea that you just need to pull yourself up by your bootstraps to the extreme. He applied that ‘can do’ attitude to every aspect of his life. And if he ever ‘couldn’t do’ it certainly wasn’t a personal failure. Confidence was this man’s middle name (actually it’s Devereaux but you get the point). If he had lived today, he would have sold a million self help books by now.

Micheaux was born, Oscar Michaux January 2, 1884. He later added the ‘e’ to his own name. He was born to former enslaved parents who when free, settled on a farm in Great Bend, Kansas. He was the 5th of 13 children. When Micheaux was young, his parents moved briefly to the city so their children could receive a better education. Soon running into financial troubles, the family had to return to the farm. At this point, Micheaux became rebellious and eventually, his father sent him to work in the city. This was where Micheaux built social skills and the work ethic that would follow him through life.

In the city (Chicago) Micheaux took several jobs, gaining new skills and confidence with every one. After a bad experience working with one company, Micheaux resolved to work for himself. He set up a shoe shine stand inside one of Chicago’s successful African American barber shops. Here he learned the basics of business. Eventually he took what was considered a prestigious job as a Pullman porter on the major railroads. By the time he left this position he had travelled much of the United States, met lots of new people and saved up a handsome amount of money. With this, he bought land in South Dakota and became a homesteader.

Here he married Orelan McCracken who would serve as the inspiration for one of his most successful creative projects – but not in a good way! McCracken and Micheaux marriage was tumultuous. It has been said, McCracken felt neglected by Micheaux which probably wasn’t too far from the truth considering his love of work. Micheaux also had a poor relationship with his in laws. While Micheaux was away on business, McCracken gave birth. Soon after, she was reported to have emptied their bank account and fled from the homestead. McCracken’s father sold the homestead they shared and kept all of the proceeds from the sale. Micheaux tried to get his wife and his homestead back but was unsuccessful.

Micheaux decided to concentrate on his creative passions. He started to write his first of seven novels. In 1913 his first novel The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer was printed. It was largely autobiographical about his life as an African American with the desire to achieve. His second book, The Homesteader, caught the attention of the manager of Lincoln Motion Picture Company who proposed it be adapted to a movie. Wanting creative control over how the adaption was made created tension in the relationship and resulted in the movie not being made. Instead, in typical Micheaux fashion, he decided to just do it himself.

Micheaux founded the Micheaux Film & Book Company. His company produced over 40 films drawing global attention. His films centered around themes of race in the United States, often holding no bars when it came to shining a light on the hypocrisy and difference in treatment between and within different ethnic groups in the United States. Themes such as lynching, job discrimination, sexual assault, mob violence, and economic exploitation all appeared in his films without apology.

“It is only by presenting those portions of the race portrayed in my pictures, in the light and background of their true state, that we can raise our people to greater heights.”

Oscar Micheaux

This occasionally meant his films drew protests and were banned from some theaters.

Micheaux died in 1951 in Charlotte, North Carolina while on a business trip (of course). His body was returned to Great Bend, Kansas where he was buried with other members of his family.

Micheaux was posthumously awarded many accolades including a star on Hollywood’s walk of fame.

Want to see more about the life of Oscar Micheaux? Consider putting the documentary film The Czar of Black Hollywood on your watchlist.

February 8th Bessie Coleman

We hadn’t heard about Bessie Coleman until this year, and gosh was that our loss. Bessie Coleman was incredible! If we were alive when she was at her most famous, we would totally be fan-girling out. Coleman ran (well technically flew) through barriers of racism and misogyny to become the first African American and Native American woman to hold a pilots license.

Coleman was born January 26, 1892 in Atlanta, Texas. She was the 10th of 13 children. Her mother African American and her father African American and Indigenous. Her family settled in Waxahachie, Texas and worked as sharecroppers as well as other jobs such as maid and laundry washers. In 1901, George Coleman, Coleman’s father, returned to Oklahoma (or Indian Territory as it was then called) to find better opportunities, but his wife and children did not follow. Bessie stayed in her small town and was educated with her brothers and sisters at a segregated school. Bessie walked 4 miles each day to attend school. Coleman was smart and at 12 was accepted on a scholarship Missionary Baptist Church School. When she was 18, Coleman took what savings she had and enrolled in Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal University in Langston, Oklahoma. But soon, savings ran out and she had to return home.

At 23 Coleman made the big move to Chicago to live with her brother John. There she attended Burnham School of Beauty Culture and became a manicurist in a local barbershop. In this barbershop she would hear stories from the World War I Servicemen, including her own brothers. This was when she was first introduced to the idea of flying. Her brother John would tease her saying French women were able to become pilots. This fascinated Coleman and soon, she would make it her mission to experience the freedom of the sky. She applied to many flight schools across the USA, but no school would take her because she was both African American and a woman. Famous African American newspaper publisher, Robert Abbott advised her to move to France. There she could learn how to fly. Abbott published Coleman’s quest in his newspaper and soon she received sponsorship to begin her journey! She began taking French classes at night because her application to flight schools needed to be written in French. Coleman was accepted at the Caudron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France.

In 1921 became the first African American and Native American woman to earn an aviation pilot’s license and the first African American and first Native American to earn an international aviation license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

After returning to the USA for a short time, Coleman realized to be able to make a living from aviation, she would need to enter the world of ‘barnstorming’ or stunt flying. Unable to find anyone to teach her in the United States, she returned to Europe and travelled the continent, learning flight skills from various different experts.

Over the next five years, Coleman built a name for herself as “Queen Bess” and became famous for her daring and death defying aero-tricks. Queen Bess became hugely popular, drawing crowds from all over to watch her fly. She used her fame to speak up for civil rights in America. She made several appearances throughout the country and refused to speak anywhere that was segregated or discriminated against African Americans. At one point, she returned to her hometown to perform. Because Texas was still segregated, the managers of the event wanted separate gates. Coleman refused to perform unless there was one gate where all would enter to watch her fly. Earnings from her various shows AND a beauty shop she opened in Orlando, allowed Coleman to eventually buy her own plane

Flying was a dangerous business and Coleman’s career wasn’t without incident. February 22, 1923 while performing in Los Angeles, her plane stalled and crashed, leaving Coleman with broken ribs, cuts and a broken leg. Being known for stopping at nothing to complete her stunt, Coleman begged the doctor to allow her to finish the show. He instead called an ambulance. While recovering, Coleman wrote in a telegram to her fans:

“Tell them as soon as I can walk, I will fly” A vow she seemed to apply to her whole life.

Three years later, would come an incident she would not escape from. Coleman’s death was heartbreakingly pointless and tragic. Flying with William Willis, her 24 year old mechanic and publicity agent, Coleman was surveying for an airshow she would later perform. During the flight, a wrench lodged itself in the engine. This prevented Willis from being able to control the steering of the plane. Wanting to be able to see the area she would be performing, Coleman was not wearing a seatbelt. When the plane flipped, she was thrown from the plane at 2000 feet. She died instantly upon hitting the ground. Willis crashed with the plane, also being killed. Coleman was just 34.

Coleman’s funeral was held in Florida before she was returned to Chicago. Her memorial ceremonies were said to have been attended by upwards of 10 000 people.

We don’t know what would have become of Bessie Coleman but we do know that it was her dream to encourage more People of Color and women to become aviators. She one day wanted to open her own school. Although she wasn’t able to make her dream come true, other people picked up her torch. By 1977, African American women pilots formed the Bessie Coleman Aviators Club. In 1995, the “Bessie Coleman Stamp” was made to remember all of her accomplishments. Now, although still only making up a small percent of flyers, there are many women of color who are continuing the legacy of Bessie Coleman – something we can be sure she would have been so proud to have inspired.

February 9th Hattie McDaniel

If you’re over a certain age (or into film at all), you’ve probably seen the 1939 movie ‘Gone with the Wind’ you’re probably already an admirer of the work of Hattie McDaniel. Although only credited with 83, she was in over 300 movies in her time!

McDaniel was the youngest of 13 children. She was born in 1893 to a family called to entertainment. Her mother was a singer of gospel music, Her older brother, Sam McDaniel, played the butler in the 1948 Three Stooges’ short film Heavenly Daze. Her sister Etta McDaniel was also an actress. She also wrote songs and performed in brother Otis McDaniel’s carnival company.

McDaniel’s acting and singing career began in high school where she recited “Convict Joe” for a contest. McDaniel performed throughout her youth in various travelling show until the 1920’s when she began a singing radio career. When the stock market crashed in 1929, McDaniel’s performance career was paused. She found work as a washroom attendant at Sam Pick’s ‘Club Madrid’ near Milwaukee. Knowing her own skill and wanting to feed her desire to perform, McDaniel was able to convince the owner to allow her to sing in what was previously a whites only stage. She soon became a regular performer.

In 1931 McDaniel moved with her siblings to Los Angeles. There she found work as a maid while she continued to look for acting and singing jobs. During the early 1930’s, McDaniel’s reputation grew and she slowly found roles in bigger movies. In 1934 landed her first major role in Judge Priest where she acted and demonstrated her singing ability. Most of her roles throughout her career were as maids or in chorus. She made friends with many celebrities during her career such as Joan Crawford, Tallulah Bankhead, Bette Davis, Shirley Temple, Henry Fonda, Ronald Reagan, Olivia de Havilland, and Clark Gable.

In 1939 she landed the role that she would be best known for, ‘Mammy’ in Gone with the Wind. Competition for this role was fierce. It’s even rumored that Eleanor Roosevelt wrote to the director requesting her own maid, Elizabeth McDuffie be given the role. McDaniel won the 1939 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for this role making her the first African American to win an Oscar. Something that would not happen again for another generation.

The hugely anticipated movie premiered in Atlanta, Georgia. Due to the racist segregation laws, McDaniel was not permitted to attend the opening night. During her awards ceremony in Los Angeles, McDaniel and her companions were required to sit at a segregated table in the whites only hotel. As her fame grew, McDaniel herself faced criticism for taking unfair as well as inaccurate roles that compounded and in some cases celebrated the stereotypical dim-witted, subservient role of African Americans in the United States. To this McDaniel was reported as saying “Why should I complain about making $700 a week playing a maid? If I didn’t, I’d be making $7 a week being one.” This furthered the perception in the Black community that McDaniel was willing to hinder civil rights progress in the United States for personal gain.

During her rise to fame, McDaniel went through significant personal pain. She experienced 4 failed marriages and despite dearly wanting to be a mother, she suffered a false pregnancy leading to a battle with depression. However she never stopped working and built a reputation for generosity, lending money to friends and strangers, performing in charitable events and raising funds for charitable causes.

Soon after a heart attack in 1950, McDaniels discovered she had breast cancer which ultimately led to her death in 1952. In her will, she wrote “I desire a white casket and a white shroud; white gardenias in my hair and in my hands, together with a white gardenia blanket and a pillow of red roses. I also wish to be buried in the Hollywood Cemetery”. Unfortunately due to racial segregation, even in death, the cemetery owner refused to allow McDaniel to be buried there. Instead, her family buried her in Rosedale Cemetery where she lies to this day.

It can’t be denied that McDaniel loved what she did. Being from the family she was, you could say she was born and raised an actor and performer. Her trailblazing achievements are referred to as inspiration for African American artists to this day.

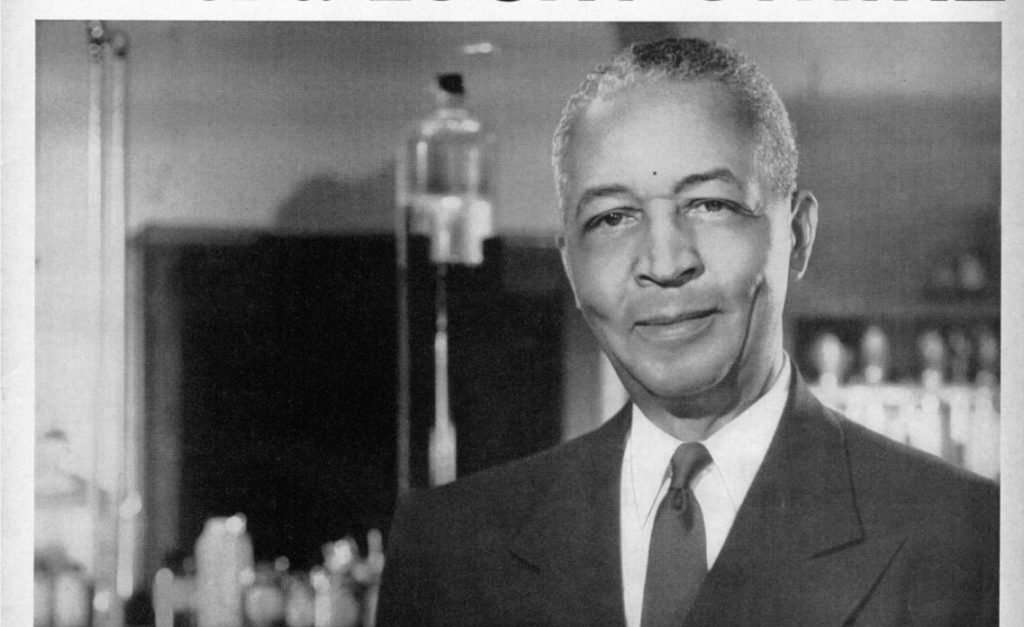

February 10th Lloyd Hall

So, take a look in your pantry and tell us how many of those spices have been sitting there since you moved into your home 10 years ago. The reason they are there and not in the trash is because you forgot they were even in there, right? And do you know why you were able to forget about them? Because some magical inventor found a way to stop them spoiling so they don’t start stinking up the whole house (the Ethylene Oxide Vacugas treatment in case you were wondering). That magical inventor was Lloyd Hall. He may not have helped our procrastination in cleaning out the pantry, but he sure has saved a lot of people from being poisoned by spoiled food and saved a lot of food waste by increasing its shelf life!

Lloyd Augustus Hall was born in 1894 in Elgin, Illinois. His father was a pastor in the church his grandfather had helped found. His mother was Isabel, a highschool graduate, something uncommon for African American women at the time.

Hall himself graduated High School in 1912, one of the top 10 of his class. There he had developed an interest in chemistry and decided to attend Northwestern University in nearby Chicago, and graduated with a Bachelors in Chemistry in 1916. He then began to pursue graduate studies at the University of Chicago while pursuing work as a chemist.

Hall’s qualifications spoke for themselves, he was hired unseen by Western Electric Company however racism resulted in him being turned away upon his arrival and a company losing out on world changing science. Several other companies followed suit, however their loss was society’s gain. Hall was hired by Chicago Department of Health Laboratories where he was quickly promoted to senior chemist.

In 1919, World War I broke out. Hall left his position for the Department of Health and became assistant chief inspector of powder and high explosives in the Ordnance Department of the U.S. Army, primarily inspecting the output of a Wisconsin explosives plant. After the war, Hall married Myrrhene E. Newsome, a schoolteacher from Macomb, Illinois. The couple had two children, Kenneth and Dorothy. That same year, Hall accepted a position as chief chemist with the Ottumwa, Iowa-based meatpacking firm John Morrell & Company. What would a meat packing plant want with a chemist you ask? Well during the early 1920’s, the food industry were trying various ways to cheaply and safely preserve food. Until this time, salt and spices had been used as a preservation technique but still resulted in large amounts of spoiling and food waste.

Hall spent the early 20’s in different senior positions and a building consultancy business until he was offered a position in the Laboratory of one of his old college classmates. Hall soon became Griffith Laboratories’ chief chemist and director of research. He remained at this company until his retirement in 1959.

Griffith Laboratories gave hall the space and resources to concentrate his research on meat preservation. After some time of experimentation and study, Hall developed a flash drying technique that would revolutionise the meat industry. During this time, meat packers would often use a combination of spices such as garlic powder and paprika to prevent meat spoiling. Although these spices probably made the meat delicious, Hall found that they would actually hasten the deterioration of meat due to the bacteria the spices carried. In developing a technique to combat these bacteria, Hall invented a technique that is still used today to sterilize hospital equipment, bandages and even cosmetics! Although this technique helped sterilize food, it was not safe for human consumption. After further research and experimentation, Hall eventually developed an antioxidant salt mixture that could be used to preserve meat and food. This and many other of Halls discoveries lead to a massive reduction in food waste, the formation of the supermarket as we know it and the ability to send food longer distances without it becoming a risk for consumption.

All while changing the world with science, Hall was also active in changing the world through civil rights activism.

Hall “…served on the Chicago Executive Committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and later on the Board of Directors of the Chicago Urban League. He served on the Illinois State Food Commission and consulted with the George WashingtonCarver Foundation in the 1940s, and worked with the Institute of Food Technologists, serving on the organization’s board in the early 1950s. During the late 1950s, Hall was active in the Hyde Park-Kenwood Conservation Community Council, an organization that worked for urban renewal in Chicago. From 1959 to 1960, Hall served as a member of the Board of Trustees of the Chicago Planetarium Society, acting as a science and education adviser to the Adler Planetarium.”

Encyclopedia.com

Towards the end of his life, Hall and his wife retired to California. Well into retirement, Hall continued to work to advance food and agricultural science working for the United Nations and the American Red Cross. By the time of his death in 1971, Hall had accumulated 105 patents! It’s without a doubt that Hall and his team changed the landscape of food and agriculture. Lloyd Augustus Hall made the world a safer place for us all to eat.

February 11th Learie Constantine

Some of our American readers may be unfamiliar with cricket. It’s not for everyone and some say, not us of course…that it may go on a tad too long. But of course, we don’t think that, it’s…thrilling. Regardless of your feelings towards cricket, it is a hugely popular sport played professionally all over the world, most directly as a result of British imperialism. This is where Learie Constantine first made his name but it wasn’t the only area Constantine was famous. He was also a lawyer, one of the leaders of change against racial discrimination in Trinidad and the United Kingdom, director of Britains biggest broadcasting stations and a long standing politician.

Born in 1901, in Diego Martin, Trinidad, Constantine was the son of a successful cricketer and over-seer of a Cocoa plantation. Constantine described his childhood as a happy one, he went to school and played cricket with his father and uncle. Upon graduating from school, Constantine began working as a clerk for one of the law offices in Port of Spain.

1920 began the start of his professional cricket career gaining a reputation for being an excellent player. In 1923 he was selected for the West Indies team and resigned his position at the law firm he was working at to start a career as a full time cricketer. Constantine had a long and successful career as a cricketer, touring many countries and many games. We won’t do his legacy an injustice by attempting and failing to understand and explain all of the accolades in cricket terms. Suffice to say, over 20 years in the game was a very long time.

During his time, Constantine played for English teams, being one of the first Black men to be awarded a contract. He and his family lived in England most of this time, wintering in Trinidad outside of cricket season. Life in England for a Black family wasn’t the easiest however despite the inevitable abusive and aggressive racists, his family were also warmly welcomed by many people of the towns he lived. Constantine learned to differentiate between racism caused by ignorance and outright racism and discrimination. This helped in his future career as a writer, politician and socilictor.

Knowing a career in cricket wasn’t everlasting, Constantine had continuously been studying and gaining experience in law. Something that he did not enjoy but pursued with the support of his family. His experience and contacts in law, led to a groundbreaking case which changed the landscape of race relations in England. This was Constantine v Imperial London Hotels. In 1943 Constantine and his family had been refused accommodation at one of the Imperial hotels in London due to their race. The manager had refused to honor Constantines booking with the flimsy excuse of not wanting the color of Constantine’s family to disturb the American guests. Constantine successfully won a case and many say this was a milestone in British racial equality by demonstrating that Black people had legal recourse against some forms of racism.

From 1947 Constantine held several high profile positions, often working as a representative for labor workers and for social welfare.

In 1954 Constantine returned to Trinidad and began a political career where he fought for Trinidadian independence and an end to the racial inequalities still present in the country. In 1956 Constantine stood for election and won in the parliamentary constituency of Tunapuna. The PNM (People’s National Movement) formed a government, in which Constantine became the Minister of Communications, Works and Utilities. In 1961 he began a role as High Commissioner which was an ambassadorial role between Trinidad and the United Kingdom. This role ended in controversy for Constantine but not without having done some good. When a Bristol bus company was refusing to employ Black staff, Constantine visited the city and spoke to the press about the issue. His intervention that helped resolve the affair was crucial in persuading the British government of the need for the Race Relations Act.

Constantine spent the rest of his life in London, writing and broadcasting on issues of cricket, race and the Commonwealth. In 1969 he became the first Black man to sit in the House of Lords. Constantine died of a heart attack brought on by bronchitis in 1971. He was returned to Trinidad where he received a state funeral.

Knowing there would be hardships, Constantine took opportunities and spoke up where he could, leading Learie Constantine to be instrumental in improving racial equality in the United Kingdom and remaining to this day, a hero of cricket fans throughout the world.

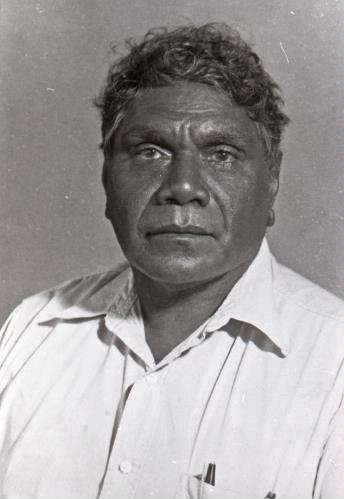

February 12th Albert Namatjira

Albert Namatjira has been called Australia’s most famous aboriginal artist. Namatjira was born in 1902 to the Western Arrernte People. Namatjira was raised in a Christian Mission when his parents adopted Christianity. Although born as Elea, when baptised, he was renamed Albert. Until the age of 13, Namatjira was raised on the mission. As soon as he entered his teenage years, he spent 6 months in the bush (Australian wilderness) for his initiation; exposing him to traditional culture and being initiated as a member of the Arrernte.

At 18, Namatjira left the Mission to marry his wife Ilkalita. Like his father, Namatjira married outside the classificatory kinship system and as a result was ostracized from his community for many years. Together they had five sons and three daughters. During this time he worked as a camel driver, a carpenter, blacksmith and stockman.

From an early age Namatjira loved art. As a child he would sketch his surroundings, and as an adult he would sell small pieces of his work to bring in extra money. It wasn’t until he was exposed to western-style painting through an exhibition, that the style of painting we know and love today started to develop. When one of the exhibiting painters returned to Namatjira’s Mission, they agreed to trade Namatjira’s cameleering and guidance for lessons in painting.

Namatjira began to paint the landscapes that he and the generations before him had walked and lived on. This in itself wasn’t unusual for artists but Namatjira’s western style but use of traditional ocre colors, made his landscapes unique. The western style appealed to European audiences and it wasn’t long before his work was globally sought.

Namatjira’s fame brought with it it’s own challenges but also highlighted glaring disparities in the application of law to Indigenous Australians. By custom and tradition, the Arrernte People lived a communal life sharing in each other’s good fortune. This meant that at one point, Namatjira found himself responsible for almost 600 of his community. There followed a series of property deals where Namatjira was the victim of cheats. Racist application of law in the Northern Australian territory meant that people of Aboriginal descent were not classed as Australian citizens and were not entitled to vote or own property. This led to Namatjira and his family living in poverty despite being one of Australia’s best known and celebrated artists. When this was publizided there was an outcry of outrage of his treatment. Wanting to save face, the government gave both Namatjira and his wife an exemption of their Aborignal status. As unpalatable as this was, it meant Namatjira were able to own land, build a house, vote and drink alcohol. Namatjira’s extended family were considered wards of Namatjira and his wife. Although this exemption would bring Namatjira and his community better living conditions, it came back to haunt him when an Aboriginal woman, Fay Iowa, was killed. Using the Welfare Ordinance of 1953 as evidence, the prosecutor of the case held Namatjira responsible for not keeping alcohol away from Iowa’s murderer. Namatjira was held responsible and sentenced to six months in prison. After negative publicity about the operation of the Ordinance this was reduced to three months.

Shortly after his release, Namatjira was taken into hospital after suffering a heart attack. While recuperating, Namatjira still painted, presenting three landscapes to the mentor who had taught him to paint all those years ago. Namatjira eventually succumbed to heart disease complicated by pneumonia in August 1959.

Namatjira’s popularity lives on to this day and his work is considered a cultural treasure. His legacy lives on in his grandson Vincent Namatjira who says:

“I hope my grandfather would be quite proud, maybe smiling down on me; because I won’t let him go. I just keep carrying him on, his name and our families’ stories.”

February 13th Zelda Wynn Valdes

If you’ve never heard of Zelda Wynn Valdes, when we tell you one of the things she’s most famous for, you’re gonna be like “WHAT?!” First let’s tell you how she got to that point.

Zelda Wynn Valdes was born Zelda Christian Barbour, 1905 in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. She began learning her trade at her grandmother’s feet, watching the seamstress sew. One day she offered to sew her grandmother a dress, to which her grandmother responded “’Daughter, you can’t sew for me. I’m too tall and too big”. Can you guess what Valdes did? You got it! She made a dress that was a perfect fit. This natural ability to “…make people beautiful”, would lead Valdes to becoming one of the world’s most sought after fashion designers.

Valdes began her career in her uncle’s tailoring shop in White Planes, NY after she finished high school. In the 1930’s she moved on to become a Stock Girl at a high end boutique. There she would slowly move up to sales and tailoring. This made her the first Black sales person in the history of the store. Valdes recalled that it wasn’t an easy time for her but she wanted to prove she could do it.

After a few years in the industry Valdes opened her own store called Chez Zelda on Broadway in Manhattan! Here she developed her signature style of low cut, body hugging, intricately made gowns which unapologetically accentuated the curves of a woman’s body. From this location, Valdes created designs for stars such as Josephine Baker, Diahann Carroll, Dorothy Dandridge, Ruby Dee, Eartha Kitt, Marlene Dietrich, Ella Fitzgerald and Mae West. She also designed the wedding dress for Maria Ellington, the future bride of Nat King Cole. Valdes famously helped define the look of ‘Bronze Blonde Bombshell” Cabaret singer Joyce Bryant. Valdes became the go to designer for any woman who wanted to turn heads.

This may have brought her to the attention of notorious playboy, Hugh Hefner. Hefner commissioned Valdes to create the infamous Playboy Bunny outfits for the staff of his gentlemans club. There is some question over whether Valdes was the sole designer of the outfits, however with their low cut, waist hugging bodices, you can see she was heavily involved. Yep! Valdes was the creator of the playboy bunny outfits!

Although the bunnies is what she is most famously known for, a bigger accomplishment came in 1970 when she was asked by Arthur Mitchell, (the first black principal dancer to perform in the New York City Ballet) to design the costumes for the Dance Theatre of Harlem. She was 65 at the time. During her time with the dance theatre, she designed costumes for over 80 productions modernizing and challenging the view of what a traditional ballet costume should look like.

Later in her life, Valdes led the National Association of Fashion and Accessory Designers, a coalition that was founded with the sole purpose of promoting black designers. Her work helped to pave the way for all black fashion and costume designers today such as Ruth E. Carter and Tracy Reese.

After a long life of forging paths unknown and literally changing the shape of fashion, Valdes passed away in 2001 at 96 years old. Her style and contribution to fashion will remain timeless.

February 14th Josephine Baker

What would you think if we told you about a woman who went from a homeless child to French resistance spy who seduced dignitaries and celebrities alike, who with her beauty and personality charmed an entire continent, lived in a French mansion, adopted 12 children, was pegged as a leader for the civil rights movement after Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated…oh also had CHEETAH!? You’d probably think we were reading from an femme fatale adventure novel. NOPE! This was the real life of Josephine Baker.

It seems like Baker was born into a life that was destined to be interesting. Her mother was an African American woman who was rumored to have been pregnant under circumstances unknown by a prominent white man of the area. Despite evidence to the contrary, Baker’s father was listed as a drummer named Eddie Carson however her true father remained a mystery until her dying day. It was into this situation on 3 June 1906, Freda Josephine McDonald was born.

Baker spent her early life in the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood of St. Louis. The family lived in relative poverty and Baker spent much of her childhood on the streets. At just 8 years old Baker was working as a livin domestic servant for white families. A job that exposed her to abuse, one employer burnt her hands when Baker used too much soap in the laundry. During this time Baker found herself in and out of homelessness, scavenging for food. To gain enough money to eat, she began a walk of life that would lead to eventual stardom – she became a dancer. First she began by dancing in the street for change, at the age of 13, she began waitressing at Old Chauffeur’s Club where she met and married her first husband (both just 13 and divorced in under a year). She met and married her second husband William Baker at 15 years old. Their marriage did not last long but she kept her married name as she had begun to find success. After persistent badgering of the manager, at 15 she was recruited to the St. Louis Chorus vaudeville show. It was through these vaudeville shows, Baker found her first taste of success.

With one of the vaudeville shows, Baker was able to travel to Paris where she fell in love with Paris and with France. Baker became an instant success with her risque and comic dances. In later shows, she was accompanied by her pet cheetah ‘Chiquita’ who would often escape and harass the orchestra. Baker became a superstar, fans from all over Europe would clamor to see her. All of her shows would sell out. She rubbed shoulders with celebrities such as Grace Kelly, Frida Kahlo Ernest Hemmingway and Jean Cocteau. She was painted by Piccasso!

When the first world war broke out in 1939, Baker was recruited by the French military to become an honorable correspondent (basically a spy) where she would use her celebrity to gather information about German troop locations and smuggle information to France and England. In 1941 she continued her Resistance work from Morocco. For her help in defeating Facist Germany, Baker received the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance and was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur

During these years in France, Baker had several relationships and marriages with men and women who were charmed and enamoured with her. Baker wanted to be a mother however suffered several miscarriages, one which almost took her life while working in Morocco. Baker would go on to adopt 12 children, living with them in a French Mansion which was occasionally opened to the public.

During the 1950’s, her popularity still raging strong, Baker made a tour of the United States. From her time in Europe, the disparities between her treatment as a Black woman in Europe and the still segregated United States became obvious with several incidences where she would not be hosted or served. At one point 36 hotels refused to host Baker and her husband, and they received several threats of violence from members of white terrorist groups. Baker became an avid activist for social change and refused to perform anywhere with a segregated audience. Baker worked with and was honored by the NAACP and became the only official speaker at Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1963 speech in Washington DC.

Baker continued to perform, work, and make waves until almost her dying day. Her death was just as romantic as her life. Baker’s last show was in 1975 honoring her 50 years in entertainment. She previously had gone through a period of despondency, feeling as though she was a ‘has been’ however this show sold out and was attended by stars such as Sophia Loren, Mick Jagger, Shirley Bassey, Diana Ross, and Liza Minnelli. It was a hit. Four days later, Josephine Baker was found lying in her bed surrounded by newspapers filled with glowing reviews of her performance. Baker lay in a coma from which she would not wake for a short time before passing away at hospital, aged 68.

Josephine Baker’s life is so full there’s no way we could do it justice in this little blog post. It’s as though she lived four full lives in one! We recommend you watch one of the movies or books that were written about her life. It’s hard to believe a person like Josephine Baker existed in the world, her life was like an epic novel, but there she was living life to its absolute fullest; and in her legacy advising us all to do the same.

February 15th Thurgood Marshall

A hammer of justice, a driver for civil rights and a formidable force in breaking through racial prejudice – this was Thurgood Marshall.

Marshall was born on July 2, 1908, in Baltimore, Maryland. His father, William and Norma, a railroad porter and a teacher. Marshall always said it was his father who installed in him the skill that would build a great career. Every night after dinner, the family would debate current events. His father would take Thurgood and his brother to watch court cases and later debate what they had seen.

Marshall was an excellent student and graduated a year early in the top third of his class. He went on to Lincoln University where as many young people, enjoyed his first fledge of freedom as an adult. This meant he neglected his studies however he was still a star of the debate team. As many people do, Marshall began to fly right after he fell in love. Marshall married Vivien Buster Burey in 1929 and began to take his studies seriously, graduating cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts degree in American literature and philosophy in 1930.

With the intention of studying law, Marshall then moved on to Law School. Although he has wanted to study law in his hometown, the University of Maryland School of Law had a policy of segregation. Their loss as Marshall instead was accepted Howard University School of Law where he graduated in 1933 ranked first in his class.

After graduating law school, Marshall began his own practice in Baltimore. Just a year after graduation, Marshall won a huge case that set his path in motion. Remember how he was unable to attend University of Maryland because of segregation? Marshall represented the NAACP case for Donald Ganes Murray, a black student who was denied entry to University of Maryland based on his race. This must have truly lit a fire under Marshall because he came out victorious against the then Attorney General who was representing the University of Maryland. As a result of this victory Marshall became part of the national staff of the NAACP.

This was just the beginning of a list of successful civil rights legal battles, literally driving change within the system. Marshall famously won 29 out of the 32 cases he argued before the Supreme Court. The idea that change needed to come from within, at times put Marshall at odds with other civil rights leaders at the time. Marshall sided with the director of the FBI when they were called out for failing to seriously investigate cases involving Black victims. Always looking for the tactical advantage, Marshall used this as a chance to “take the heat off the NAACP” and create a closer collaboration with the FBI.

This gave Marshall a level of trust within the U.S. government that led to high ranking positions. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961, an entirely new seat. He was appointed to be the United States Solicitor General, which made him the first African American to hold the office. Then, on June 13, 1967, President Johnson nominated Marshall to the Supreme Court, again the first African American of 96 to hold the position.

Marshall was on the Supreme Court for 24 years, contributing to progresses in labor rights, civil rights, human rights and rights of the individual. He famously said:

“You do what you think is right and let the law catch up”

Marshall retired from the Supreme court in 1991 due to declining health. He passed away of heart failure just two years later at the age of 84. Thurgood Marshall’s influence and inspiration lives on to this day, in fact his Bible was used by Vice President Kamala Harris at her inauguration in Washington on January 20, 2021 when she was sworn into office! His 60 year legacy led to progress against inequality in American society. His life and legacy shows us how important it is to celebrate our progress but never stop fighting against racism, segregation and injustices in human rights.

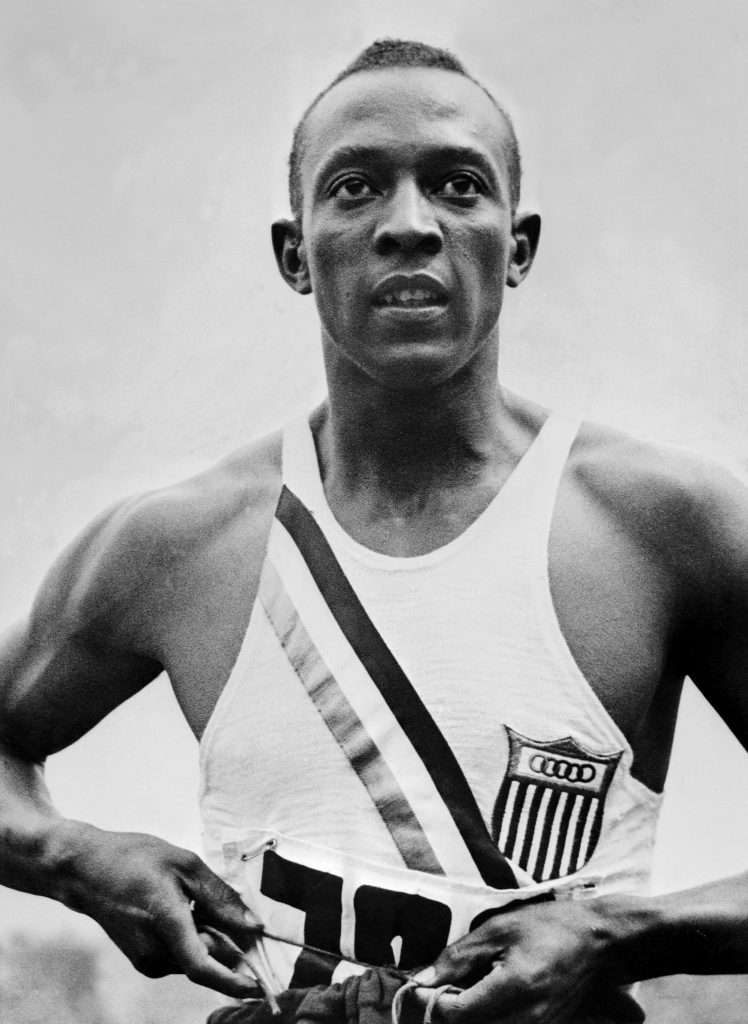

February 16th Jesse Owens

1936 was a bad time in history. Facism had taken its death grip across the world and we all know what happened next (if you don’t you definitely should have paid more attention in history class). There was a bright spot during this atrocious period of amplified hate, his name was Jesse Owens and the place was the German Olympic Games.

Jesse Owens (known as JC to family) was born in Oakville, Alabama on September 12th, 1913, the youngest of 10 children. At the age of 9, he and his family were a part of the Great Migration as African American families left the segregated south for urban and industrial opportunities in the North. The family settled in Cleveland, Ohio where Jesse attended school. Interesting fact, when Owens was asked his name by a teacher, in his strong southern accent Owens said “J.C”. The teacher heard “Jesse” and the name stuck!

During his schooling, Owens joined the track and field club. Owens would often credit his junior high school coach with the development of his skills and love of running. As Owens worked after school, his coach would allow him to practice before school instead. Junior high was also where Owens met his wife Minnie. They had three children together and remained married until Owen’s death in 1980.

When Owens started high school, he began to gain attention for his athleticism. He equaled the then world record of the 100 yards dash and the long-jump at the 1933 National High School Championship in Chicago. There followed the breaking of world records again and again. Despite his successes, Owens was not eligible for a scholarship and had to work part time to pay for his studies. When the teams travelled, he and his fellow African American team mates had to stay in ‘Blacks Only’ accomodation, and were restricted to ordering take out or eating at ‘Blacks Only’ restaurants.